A sourdough bread starter is essentially a culture of wild yeast and bacteria. You’ll often read about how these cultures produce lactic acid, acetic acid, and various other byproducts, but what does that really mean for a beginner baker? Let me offer you a perspective that will help you truly understand how sourdough works and the processes involved.

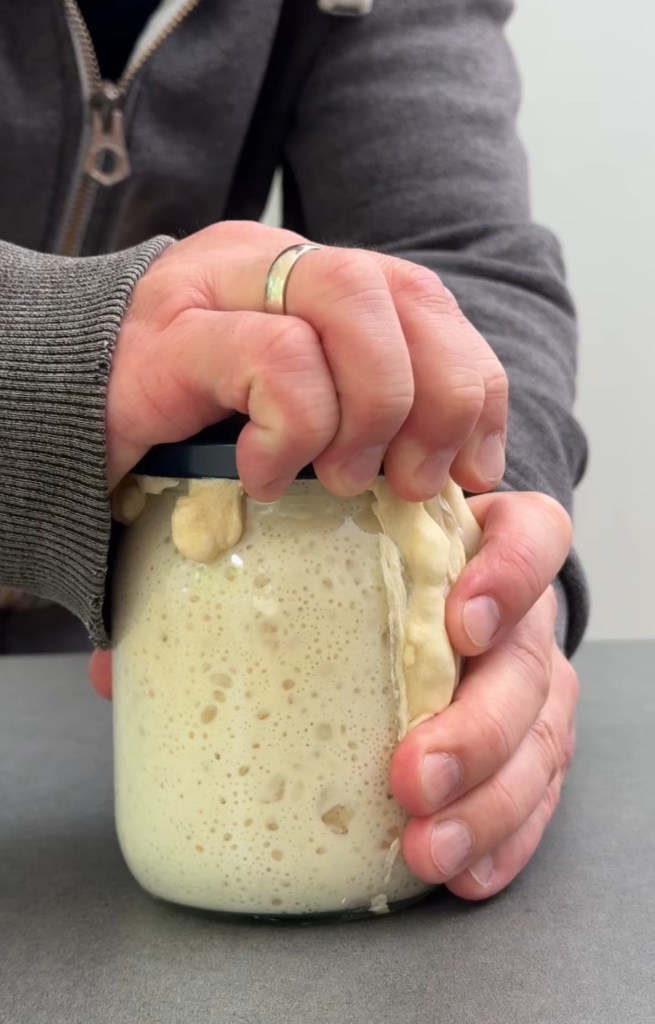

At its core, a starter is just a mixture of flour, water, and naturally occurring yeasts. I won’t go into detail here about how to make a starter, as we’ll assume you already have one. So, you mix your starter with water and flour, creating a thick mixture. But how does this mixture transform into bread? Bread is light, airy, and full of air pockets—at least, it should be! Meanwhile, your sourdough starter is a thick, almost pudding-like substance. What exactly is happening here?

The Process Behind Sourdough: A Simple Analogy

To help you visualize this, I like to use an analogy from a completely different industry: the production of sponges, the kind you use for cleaning. A sponge starts as a thick liquid made from synthetic material. In a heated environment, this material turns into a dense liquid, similar in consistency to your bread starter or dough just after mixing the ingredients.

To give the sponge its light, porous form, gas is injected into the material, causing it to expand and take on its final shape. The gas creates tiny bubbles that, once the material cools and solidifies, give the sponge its unique texture.

In sourdough bread, we don’t inject gas directly, but a similar process takes place naturally. Instead of technology, we rely on the ancient process of fermentation. The wild yeast and bacteria in your starter consume the sugars in the flour and release carbon dioxide. This gas forms small bubbles, which eventually create the “crumbs”—the airy structure inside the bread. These bubbles are also responsible for the increased volume of your starter or dough, which can rise to double or even triple its original size.

Once you understand this process, it becomes clear: all you need for successful fermentation are wild yeast cultures, flour, and water. The higher the temperature, the faster this process occurs.

What Happens When Fermentation Stops?

Let’s return to our sponge analogy for a moment. If you stop injecting gas into the synthetic material, it will cool down and lose its airy, expanded form. Similarly, if your starter runs out of fresh flour to “feed” on, it will stop producing carbon dioxide. As a result, it deflates and turns back into a thick, dense mass—filled with hungry yeast, waiting for a new supply of flour.

In the case of bread, timing is critical. You need to monitor your dough’s rise carefully. The bread should go into the oven at just the right moment, when almost all the flour has been fermented by the starter. If you miss this window, your bread may collapse, or if baked in a loaf form, it might spread out flat like a pancake.

Timing, Experience, and Observation

For beginners, it’s essential to follow the recipe closely, paying attention to the recommended times and temperatures. As you gain experience, you’ll learn to adjust recipes based on your environment, making small tweaks to suit the specific conditions in your kitchen.

You may find the sponge comparison unusual, but the concept of incorporating gas into food products is actually very common in the food industry. Take, for example, carbonated beverages or the use of baking powder in pastries. Baking powder, invented in the mid-19th century, is widely used in the baking world. When you mix it with flour and water, a chemical reaction occurs, producing carbon dioxide, which gives the dough or batter its light, fluffy texture.

This is essentially a shortcut—a way to mimic the natural fermentation process. While it saves time, it comes at a cost to our health. Artificially leavened flour is harder for the body to digest and doesn’t provide the same nutritional benefits.

The Health Benefits of Fermentation

Fermentation, on the other hand, is a natural process that has been used for thousands of years. Bread made through fermentation is healthier and easier to digest. The fermented flour is more easily absorbed by the body, and our system is better able to extract the nutrients from it.

In conclusion, understanding the process of sourdough fermentation helps you take control of your bread-making. As you become more familiar with the behavior of your starter, the timing of fermentation, and how temperature affects it, you’ll not only bake better bread but also enjoy a healthier, more digestible product.

Happy baking!